The Lord’s Prayer in the Middle Ages

The Lord’s Prayer is the prayer that Christian tradition traces back to Jesus himself in the Gospel of Matthew and Luke. This has made it a central aspect of Christianity as the ideal prayer from the time of the early Church onward. For that reason, it is an exciting object of interdisciplinary research:

-

As the ideal prayer (Lk 11:1-4), the Lord’s Prayer is characterised by great historical continuity. However, in order to stay relevant in the face of changing cultural contexts and demands over centuries, it had to be constantly reinterpreted. Examining this text, therefore, provides insights into theological change as well as that of time-specific religious experiences and practices. Furthermore, it provides the opportunity for diachronic comparison.

-

At the same time, praying the Lord’s Prayer has been understood from the beginning as a task for every Christian (Mt 6:9: “This is how you should pray …”) and so ecclesiastical authorities used the prayer as a normative framework for elementary Christian knowledge, instruction and even quality control. Consequently, examining the Lord’s Prayer will always result in interesting cases of theological reflection, catechetical instruction and lived practice. It provides insights into the expectations of different social groups with regard to this text and encourages us to look beyond traditional lay-clerical boundaries. Moreover, it forces us to recognise the diversity of theological and pious historical phenomena that existed between lived practice and written theory.

On the project

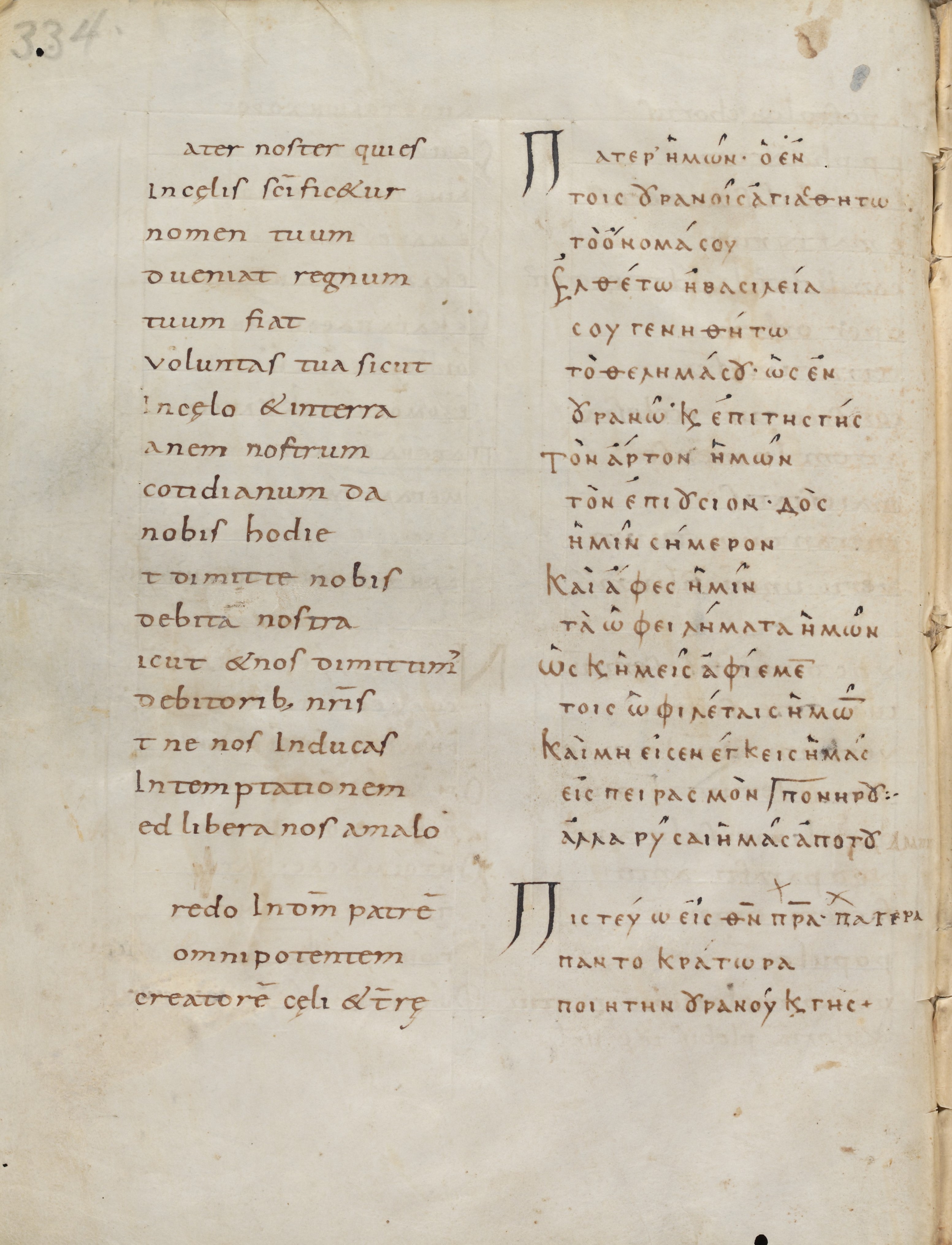

Our project ‘Pater NOSTER - Understanding and Use of the Lord’s Prayer in the Middle Ages (800–1500)’ aims to examine two dimensions: with ‘Understanding and Use’, we emphasise that we are starting with the theological reflections of known (and unknown) interpretations of the Lord’s Prayer in the Middle Ages. At the same time, however, we try to broaden our scope by going from these classic texts to hitherto unexamined contexts of use and target groups (both through the texts themselves and the manuscripts in which they were copied). We are particularly interested in the interplay between literary creations and theological influences, in the “Sitz im Leben” of prayer in catechesis and liturgy, in practical piety within and outside monastery walls, and in marginalia and annotations, the development of vernaculars, etc. The capitalised ‘NOSTER’ visualises the underlying second level of appropriation practices: We are dealing with multiple Lord’s Prayers, which we encounter in the manifold of requests, appropriations and uses of the Lord’s Prayer at different points in time and by different social groups in our evidence.

To gain access to these medieval contexts, we use manuscript research and focus on its cultural and material-historical aspects. The St. Gallen manuscript collection, which is unique for its continuity, enables us to examine contexts of use of the Lord’s Prayer in numerous codicological compositions as well as in traces left by their creators and users. This does not mean, however, that by selecting this archive we are restricting ourselves to a male monastic context only, as books from women’s convents but also private collections have also been incorporated. What is more, the monastery was part of vast networks of exchange and its monks also took part in administering religious instructions and pastoral care, through which the prayer effectively broke down the cloister’s walls.